Since her 2012 YA novel Seraphina, Rachel Hartman has been regularly one-upping herself. The story of a half-dragon musician learning to accept herself, Seraphina seemed perfect. Its sequel, Shadow Scale, astonished me by being even better, a bigger, broader book that filled in the world through which Seraphina walked.

Hartman followed that with Tess of the Road, which handed the narrative to Seraphina’s stubborn little sister. Tess is a book that’s like a long conversation with a stern but understanding friend, one who knows all your weaknesses and insists that you see your strengths anyway. It’s a book about setting out to find yourself in the world, and beginning to find out how much more world there is than you ever expected.

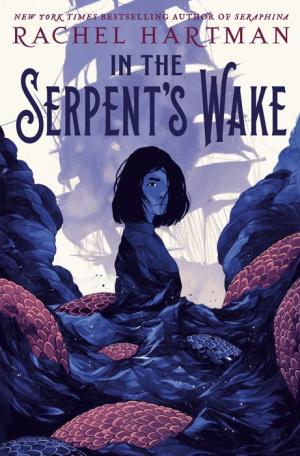

Now, in Tess’s sequel, In the Serpent’s Wake, Hartman takes the pattern from her first duology—a personal story followed by one with a wider scope—and recuts it, altering it into something even more expansive. It’s still Tess’s story, but she’s sharing it with more characters, more lands, more mistakes, and so many more ways of understanding the world.

At the end of Tess of the Road, our heroine was planning to set sail with Countess Margarethe (Marga for short), a lady explorer to whose expedition Tess attached herself and her friend Pathka. Pathka is a quigutl, a small sort of dragon-kin creature with the ability to change gender and also a great skill for creating interesting devices. He shared Tess’s path, in the first book, because he was seeking a World Serpent, a creature out of myth that turned out to be very real—until Tess’s report on its existence led a group of scientists to seek it out and, well, kill it. For complicated reasons, this had adverse effects on Pathka, and now he and Tess seek another World Serpent—one who lives at the bottom of the world.

Buy the Book

In the Serpent’s Wake

In the Serpent’s Wake helpfully starts with a recounting of Tess’s adventures in what I could only read as a song; sure, it could be a sort of epic poem, but the rhythm feels more like it might be the kind of thing a group of sailors would sing at the tavern while deep in their cups. All the same, I reread Tess before diving into Serpent, and recommend revisiting it if you can.

For one thing, Will returns. The obnoxious young lad who did Tess dirty when she was just a girl is, alas, now Marga’s beloved, and Tess struggles with whether or not to tell her new sort-of-friend about Will’s past. Former seminary student Jacomo, once Tess’s enemy and now her friend, is also on board Marga’s ship—which is not the only expedition seeking the southern Serpent. A boat full of dragons is on a similar quest, and one member of that party is the scholar Spira, who also figures into Tess’s past. Her guilt about how she and Will treated Spira is strong and present, and it underscores one of the novel’s deepest themes: No one owes anyone else their forgiveness. Not an individual, and not a whole people.

Tess’s duology is a story of unlearning as much as it’s a story of learning. Learning that she could stand on her own two feet involved unlearning the things her family had decided were true about her. Learning that the world is full of more cultures than she ever knew involves unlearning a lot of assumptions and expectations and oblivious ideas. Where Tess was personal, Serpent is … international. Global. And strongly, pointedly anti-colonialist.

The seas on the way to the south are full of islands, and those islands are full of people—people who were there long before the colonizing Ninyish arrived, determined to “civilize” these lands. The different peoples of the islands have their own religions, practices, ideas about leadership and how to be in the world; some go to war alongside tigers, while others commune with the sabak, marine creatures with a collective mind and memory (and a connection to the World Serpent). The Ninyish colonizers don’t see any of this. They see lands to dominate, forests to clear. Hartman’s protagonists see people who need help—but seeing the island folk as victims isn’t helpful, either. Good intentions are no guarantee that a person will do the right thing, though as Seraphina tells her little sister, intentions are useful, “not to absolve you, but to goad you into doing better next time.” (You might read this book as a sort of mirror image to Frances Hardgine’s The Lost Conspiracy, which tells the story of a colonized island from the perspective of the native people; here, we’re with the colonizers as some of them begin to understand their complicity.)

Hartman never forgets that Tess is a teenager in a complex international and political web, playing multiple roles for which she is untrained (on top of trying to help Pathka, she’s quietly spying for the queen of Goredd). She also never forgets the age differences between Tess and Jacomo and Marga, who all run up against their own flaws and biases, stumbling when they want to run to someone’s aid, struggling to reconcile who they’ve been with who they’re each becoming—and everything they learn. Very believably, Marga, who’s been fighting against a sexist society for all her (somewhat older) life, takes a bit longer to realize that experience fighting one battle doesn’t mean she knows how to lead a different one.

This is a book that understands that coming-of-age doesn’t just happen all at once, but is something we do over and over again; Marga has her moments, just as Tess and Jacomo do. And coming of age isn’t always about reaching goals and triumphing. Here, it’s about learning when to let go; about not getting what you want; about recognizing when you’re trying to hold on to someone else’s story and neglecting your own. Hartman’s narrative is full of surprises both subtle and breathtaking, and the process of uncovering them is what makes this book such a joy. There’s a dragon discovering her true self and what she’s capable of; there’s a warrior with a tiger and great advice about periods; there are the katakutia, who travel with the sabak and immediately became one of my favorite fantastical creations ever.

And there’s Tess, who is the heroine I could barely have imagined I needed when I was young—and who I still need now. Headstrong and impetuous and driven to help people, she’s also still a kid, and one raised with a fraught mix of privilege and deep trauma. What she learned in Tess of the Road taught her how to make her own road, but her journey in Serpent’s Wake is a reminder to walk that road with humility.

A tale within a tale runs through In the Serpent’s Wake like a bright line of thread: the story of Vulkharai, a boot-maker who falls in love with a tiger. It means something different to each nation that tells it; it means something different to each character who hears it. It’s a reminder that a story can have one outcome and a thousand meanings, and that a person can have one life and a thousand stories. What counts as a mistake or a triumph, a way to save or a way to harm, a way to love or a way to fail—none of these things are concrete.

Hartman fills her pages with nuance, with people struggling to do the best they can with what they’ve been given and what they’ve learned. “Tess of the Road is astonishing and perfect. It’s the most compassionate book I’ve read since George Eliot’s Middlemarch,” Amal El-Mohtar wrote of Tess’s first tale. I didn’t think it was possible to top that novel, with its huge heart and its perfectly flawed adventurers. I was—joyfully, gratefully, delightedly—deeply wrong. At first, I didn’t want to share Tess’s story with all these other voices and characters, but page by page, voice by voice, Hartman makes the case that that’s what a story is: all the voices and people who hear and tell it. And this one—resonant, illuminating, brilliant and wise—needed to be told by a chorus.

In the Serpent’s Wake is published by Underlined, an imprint of Random House Books for Young Readers.

Read an excerpt here.

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.